ANCSA: an impossible challenge achieved

Young state, oil discovery, and DC hero help secure settlement Alaska Native Claims – October 12, 2021

Last updated 1/6/2022 at 2:15pm

Courtesy of Willie Hensley

People associated with the Alaska Federation of Natives and others in the office of Howard Pollack in Washington D.C. Standing (left to right) George Gardner, Roger Conner, Emil Notti, Flore Lekanof, Cliff Groh, Rep. Barry Jackson, Rhoda Fox, and Morris Thompson. Seated (left to right) Rep. Willie Hensley, Pollock and Laura Beltz Bergt.

President Richard M. Nixon signed the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) in 1971, exactly 230 years after Captain Vitus Bering's Second Kamchatka Expedition finally sighted land in Alaska offshore from what is now Mount Saint Elias in 1741.

In the years between, the 70,000 or so Unagan (Aleut), Sugpiaq, Yupik, Inupiat, Athapascan, Tlingit, and their descendants began to experience extreme changes brought on by Russian and American firepower, disease, religion, commercial exploitation of sea otters, fur seals, whales, walrus, salmon, copper, gold, and timber.

Colonialism was not a word that my generation used or even understood.

Historians almost always look at history from the perspective of national interests and personalities, and the impacts and consequences on the indigenous inhabitants are either ignored, whitewashed, or forgotten.

In Alaska, the indigenous inhabitants had occupied and controlled their territories for millennia, developed cultures compatible with their environments, governed, warred, traded, and celebrated life –even in the extreme cold of the Far North.

In the case of the Inuit, their language and culture extended from the North Pacific (Kodiak Island) clear across the Arctic to Hudson's Bay, parts of Quebec and Labrador, and on to Greenland.

Doctrine of Discovery, ecclesiastical blessing

The rationale used by the Spanish to take foreign lands was the notion of "discovery."

In 1493 Pope Alexander VI issued the Papal Bull "Inter Caetera" to ensure the Spanish had exclusive rights to lands discovered by Christopher Columbus a year earlier. The Bull stated that "the Catholic faith and the Christian religion be exalted and be everywhere increased and spread, that the health of souls be cared for and that barbarous nations be overthrown and brought to the faith itself."

The Pope declared that all lands one hundred leagues west of the Azores and Cape Verde Islands belonged to Spain and that it had exclusive rights to all territories and trade. Others had to secure a special license from the Spanish Government. Any lands not inhabited by Christians could be claimed and exploited by Christian rulers.

In reality, the Pope had authorized and blessed what became a reign of terror among the citizens of Hispaniola and Central and South America.

This notion of discovery became part of the foundation of American law when Chief Justice Marshall used the principle in the Johnson v. McIntosh case in 1823. Indigenous Americans, including Alaska Natives, had "aboriginal title" or a right of occupancy, which could be extinguished by the claiming sovereign nation. The Indian nations could only deal with the sovereign in ceding lands through treaty and were not free to dispose of lands to states or other third parties.

All this legal and ecclesiastical history was unknown to us when the fight over Alaska lands came to a head in the 1960s. In retrospect, several realities that helped to bring about a land settlement:

• Alaska Natives' underlying aboriginal title ownership had never been extinguished.

• Billions of barrels of oil were discovered in Prudhoe Bay in 1968, and a pipeline across Alaska was necessary to bring the oil to market.

• Alaska did not have enough revenue to run what little government it had.

• Alaska needed the land and the oil revenue to survive as a state.

• The United States needed the oil.

• Alaska Natives were united in their desire to control their own land despite internal differences.

• The United States Congress, controlled by the Democrats, was open to a settlement.

• Richard Nixon, President-elect in 1968, was convinced that American Indians and Alaska Natives deserved "self-determination" and he backed the passage of legislation.

Mike Gravel, supported strongly by village Alaska, defeated Sen. Ernest Gruening in 1968. Gruening was a staunch opponent of Alaska Natives securing land and had done nothing to resolve the issue. He opposed the creation of any indigenous institutions.

Alaska mining and business opposition

One of the most vociferous opponents of any kind of land claims legislation was the Alaska Mining Association. Its president, Leo Mark Antony, and George Moerlein, chair of the association's Land Use Committee, were vocal and unyielding in their negative position.

Moerlein, in his testimony to a Senate committee in 1968, said, "... to grant their land requests may bring the continued development of Alaska's natural resources to a standstill." He also stated that "I submit to you that neither the United States, the State of Alaska, nor any of us here gathered as individuals owes the Natives one acre of ground or one cent of the taxpayer's money."

Another individual opined, "If given land, with the stipulation in the original papers, i.e., 40 million acres, this will absolutely cause the economic collapse of the State of Alaska." (Robert E. Curtis letter to a Senate committee.)

Emil Notti, President of the Alaska Federation of Natives, remembered when Don Dickey, Executive Director of the Chamber of Commerce, ran around a convention with a cowboy hat on with an arrow through it, mocking the land claims of Alaska Natives.

As Executive Director of the AFN, in December 1969, I found it necessary to attack the Chamber of Commerce for raising "unjustifiable fears about the settlement we seek and our legislative program." I charged them with having "limited vision and are threatening and pressuring our Congressional delegation to cease efforts to work out a compromise land claims package."

The chamber was also pushing for small acreages adjacent to villages and opposed the overriding royalty-which was a key element of the financial package being developed.

Challenging colonial mentality

From the beginning of the land claims struggle in the 1960s, only the Alaska Natives had any hope that the federal government might just reverse itself and convey land to its first citizens. It was a complete long shot, after all, the country had spent 200 years taking lands from Indian nations and paying them a pittance-if at all.

In the words of the historian Hubert Howe Bancroft, "On the whole, the people of the United States have not paid an exorbitant price for the ground upon which to build a nation. Trinkets and trickery in the first instance, followed by some bluster, a little fighting, a little money, and we have a fair patch of earth, with good title, in which there is plenty of equity, humanity, sacred rights, and star-spangled banner. What we did not steal ourselves we bought from those who did, and bought it cheap."

The Federal Field Committee (FFC), headed by Joseph Fitzgerald, was set up to help Anchorage recover from the devastating 1964 earthquake. They were to use their competent staff to coordinate the use of federal dollars in the most effective way.

Fitzgerald and his staff were contracted by Sen. Henry Jackson, Chairman of the Senate Interior Committee, to do a study of the Alaska Native land claims – the first such study in over a century. Their product was a six-pound, 569-page behemoth, but it gave credence to the Native land claims and suggested a $1 billion settlement over a ten-year period, but only 4-7 million acres of land.

In retrospect, the FFC was, in reality, proposing to use the settlement as a mechanism to destroy the various Alaska Native cultures. They saw the villages as "racial enclaves" that would prevent Alaska Natives from joining mainstream Alaska.

The FFC was trying to "individualize" the settlement and provide small tracts for homesites and subsistence lots. Fitzgerald's allocation of land would provide a township (23,040 acres) and would go to a state municipal entity. His mechanism for management was a Presidentially appointed Development Corporation for all Alaska Natives initially set up as a non-profit but to revert to a for-profit corporation in 10 years. The Native stockholders would be in control of the directors, but by the tenth year, the stock would then have to be sold in the open market and Alaska Natives would no longer be in control. Alaska Natives would end up owning nothing but the stock over which they would have no control.

AFN had a real challenge in beating down this proposal as it would have Alaska Natives in control of nothing – land or money. There would have been no village or regional corporations had the FFC's approach been adopted. The FFC proposal clearly reflected a colonial mentality.

I knew the staff personally, and it was a sad realization that they had little confidence in the Alaska Natives' willingness and ability to manage their own resources and were trying to take us down the road of extinguishing our cultural identity. But it was not clear at the time whether they were reflecting Chairman Henry M. Jackson's perspective or their own. If the former was the case, we had a huge challenge in preventing their ideas from taking root in the Congress.

To me, we were seeking land to be able to continue our way of life. The financial aspect was important but not the overriding objective. I realized from my research that paying off the Indians for their lands was the historic settlement approach and that we had to make land the foremost issue for Alaska Natives.

A DC hero emerges

Secretary Stewart M. Udall was a hero to Alaska Natives and a pariah to Alaskan politicians for his decision to cease interim conveyances to the State of Alaska when those lands were being claimed by indigenous Alaskans who had occupied their lands for millennia. He was, after all, the trustee for Indian reservations, reserves, allotments, and restricted townsites. It appeared that he did not want to be the authority to ignore Alaskan indigenous ownership rights and dispossess them of their lands when he was supposed to be protecting us. After all, the Congress had included the "disclaimer" clause, which stated that the state disclaimed all right and title to "any lands or other property (including fishing rights), the right or title to which may be held by any Indians, Eskimos, or Aleuts ... or is held in trust for said natives ... shall be and remain under the absolute jurisdiction and control of the United States until disposed of under its authority ..."

From the Treaty of Cession in 1867 to 1959, despite all the laws that had been passed in those intervening years, our sovereign, the United States, had never extinguished Alaska Natives' underlying title. However, had Sec. Udall signed the interim conveyances, that act would have been an extinguishment of our aboriginal rights.

As a non-lawyer student in 1966, I realized the danger that we were in. If there was ever a chance to turn 200 years of American history around on this issue, we had to stop the state selections. Secretary Udall, a westerner whose family was intertwined with the Native American world, precipitated a crisis for the new state, and Governor Hickel fought back furiously – legally and politically. But Udall stuck to his guns and instituted the "superfreeze" the last week he was in office before the Nixon administration took over, with our nemesis, Governor Hickel, slated to take over the department that had provided us the leverage to encourage the Congress to act on our claims.

Despite Udall's staunch support for Alaska Natives and his willingness to offer ideas to move forward with legislation, the Department of Interior's ideas were also rooted in colonial notions of how to deal with "the Indians":

• Indian reservation land was held in trust for the tribal members.

• Nothing could be done with the land without approval of the Department.

• Tribes had to be recognized by the department to qualify for the myriad of programs to enhance the material life of the Indians.

• The country was divided into "Areas" with a director overseeing the tribes in his jurisdiction and he, in turn, reported to the Commissioner of Indians Affairs (later the Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs).

Udall's department's initial proposal in the spring of 1967 was for 10 million acres of surface land for the villages; the land was to be held in trust for 25 years; compensation would be via the Court of Claims with a date of "taking" as of 1867 ($7.2 million); the Department would control the proceeds.

There was virtually no support for Udall's initial proposals.

Land Claims Task Force

In the meantime, there was a stalemate. The AFN board had no funds to meet or do analysis and the state was stymied from finalizing their hoped-for land conveyances to keep the state solvent.

Not clear at the time was this reality: no legislation was going to pass Congress to resolve the issue unless 1) the state was an active player in the negotiations and 2) the Alaska Natives had to be united and offering ideas that had the potential of being supported by the State and our congressional delegation.

We agreed to let Governor Hickel appoint the entire AFN board to the new Rural Affairs Commission to enable AFN to have funds for travel, hotels, and meals and to solidify its position on a settlement. This became known as the Land Claims Task Force. They elected me Chairman and authorized me to select a drafting committee which, under time pressures, came up with recommendations to the Governor, the legislature, the Washington delegation, and the White House.

This entity was as close as we came to a tripartite negotiation. The group was state-appointed but in addition to AFN representatives, there was always an Interior Department official, Assistant Secretary Robert Vaughn, in the discussions as well as Governor Hickel's hired consultant, flamboyant Edgar Paul Boyko.

The challenge was to come up with ideas that the state could respond to and to be prepared to present our recommendations to Senator Jackson's Interior and Insular Affairs Committee in February 1968.

The Task Force submitted its recommendations to the state in January and proposed a four-part settlement:

• A grant of 40 million acres of land in fee.

• A 10% royalty interest in outer continental shelf revenues as suggested by Secretary Udall with an immediate payment of $20 million.

• A state royalty interest of 5% on state lands.

• A license to use surface lands under occupancy and use by Alaska Natives.

• Objectives were to avoid litigation, if possible; grant present property interests; avoid state and federal control; avoid "freezing the villages in history"; spreading the benefits from royalties widely; and utilizing modern corporate forms in business enterprise.

These ideas were designed to minimize state opposition to a land settlement because without the state concurrence, our delegation would be stymied in moving forward. The recommendations were well received and even resulted in the passage of a bill by the legislature approving a $25 million payment contingent on lifting of the land freeze. It became a dead letter but it helped move the state and the citizens toward a positive outcome.

The Task Force was able to secure Governor Hickel's support for a 40-million-acre settlement. That was a significant victory as he enabled other actors on the political scene to increase their support on the higher number rather than the mediocre acreages offered in various bills. His support for a state royalty interest was also very significant, as well as the support for the corporate vehicle for management.

The work of the Task Force definitely helped move the entire prospect for a land settlement forward and provided ideas that eventually emerged in the federal legislation.

To the horror of the Alaska Native leadership, Governor Hickel was nominated by President-elect Richard Nixon to be the nation's Secretary of Interior, replacing our hero Secretary Stewart Udall.

We knew that Hickel's objective was to eliminate the land freeze and authorize a corridor for the trans-Alaska pipeline that the oil industry, Alaska, and the nation needed for their financial and energy security. We had successfully turned Governor Hickel toward positivity in dealing with the land claims issue, but we knew we had to keep the land freeze to keep the Congress' feet to the fire and come up with legislation.

The Alaska Federation of Natives took up a collection and sent Emil Notti, Eben Hopson, John Borbridge, and myself to Washington to see if we could secure a commitment from Hickel to maintain the freeze while we all worked to get a bill passed by Congress.

In the meantime, a "Truth Squad" of Alaskans chartered a plane to Washington to tell the legislators what an excellent person Hickel was – some of our AFN board members were willing to see Hickel as Secretary of Interior without a commitment on maintaining the land freeze. Under the pressures, some of our AFN board members were beginning to crumble.

Keeping the land freeze was an impossible hope as Hickel had fought the land freeze tooth-and-tong as Governor, and we doubted that he would change his mind as Secretary of Interior. His commitment to Indian America was not as strong as Udall's. Or perhaps, he saw Alaska failing as a state without the oil revenues that the pipeline would bring.

We were unsuccessful in getting his commitment, so we appealed to Sen. Jackson and the Interior Committee to secure his commitment to the freeze to give Congress a chance to pass a bill. It was a great sigh of relief when Hickel, to save his nomination, finally conceded under questioning by Sen. Jackson, that he would not tinker with the land freeze without consulting the Chairman and the committee.

Without the land freeze, we felt that Alaska Natives' hope for a land bill was toast, and we would be forgotten and shunted off to the Court of Claims where any land conveyance was absolutely out of the question and payment made in pennies an acre, if at all.

Finally, after five frenetic, pressure-filled years, President Nixon signed Public Law 92-203 on December 18, 1971, "An act to provide for the settlement of certain land claims of Alaska Natives, and for other purposes."

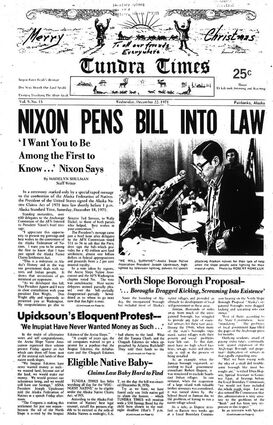

Tundra Times provides Alaskans with news that President Nixon signed the Alaska Native Claims Act into law.

We all know the broad outlines of the settlement: a payment of $962.5 million, conveyance of 44 million acres of land in fee simple; the establishment of 12 regional corporations in Alaska and nearly 200 village corporations to manage the land and funds, a provision that 70% of revenues from land resources be distributed among all 12 regional corporations; and one half of the amount received by the regions would be distributed to the village corporations within its boundaries, and for pioneer Alaskans, they finally secured, in Section 4(c) an extinguishment of all claims based on aboriginal right or title.

To the horror of all Alaska Natives, absent from the bill was any provision for continued use of the land for hunting, fishing, and trapping – the primary reason many Alaska Natives pushed for the land settlement. That challenge was dealt with in 1980 in a separate bill.

Find out more about how NANA Corp., the ANCSA regional corporation for Willie Hensley's Northwest Arctic home, utilized the ANCSA corporate structure as a tool to create economic opportunities at Alaska Natives utilize new corporate tool in Alaska Native Claims.

Reader Comments(0)